The Anatomy of Bamboo

Strap in, you’re about to peek inside of the full AuDHD inner nerd brain of @BexBunny_ (Me, hello!) and the level of research that went into making sure Shibari Lounge is as risk-aware as it can be. Understanding how things are built, exactly what we’re using, and what we’re supplying and selling at Sakunawa: The Shibari Shop feeds into my own risk profile too.

I’m incredibly passionate about tying and being tied with bamboo. There’s something about it that feels deeply alive. It isn’t just a prop; it’s a partner in the scene. Rope can have so much flexibility - it moves, shifts, and adjusts with you… but when you introduce bamboo, there’s a new kind of dialogue.

The rigidity of the pole contrasts with the softness of the rope, creating this beautiful juxtaposition of push and pull. There’s an extra layer of restriction - a freedom intentionally taken away… that somehow deepens the surrender. The slight flex under tension, the faint creak as the rope settles, the pressure building where bamboo meets skin - rope, limbs, and bamboo compacted into one delightfully bound package that lets you sink into that glorious, held and supported place where everything seems to breathe together.

When I tie with it, I feel that same balance: between control and trust, between tension and stillness. It’s a material that responds, and learning to read it (and my partner of course) changes how I tie everything else.

So, without further ado, from one rope enthusiast to another, I hope you enjoy this in depth dive on The Anatomy of Bamboo!

Understanding strength, structure, and safety for shibari use

At Shibari Lounge, bamboo isn’t decoration — it’s an essential, load-bearing part of our suspension points and our teaching practice. Every pole we use has been hand-selected, cut, and prepared for human weight and movement.

When your safety depends on the material above you, knowing bamboo’s anatomy matters. Here’s what to look out for when suspending from, or with, bamboo at home, at Shibari Lounge, and at studios all around the globe.

What is Bamboo?

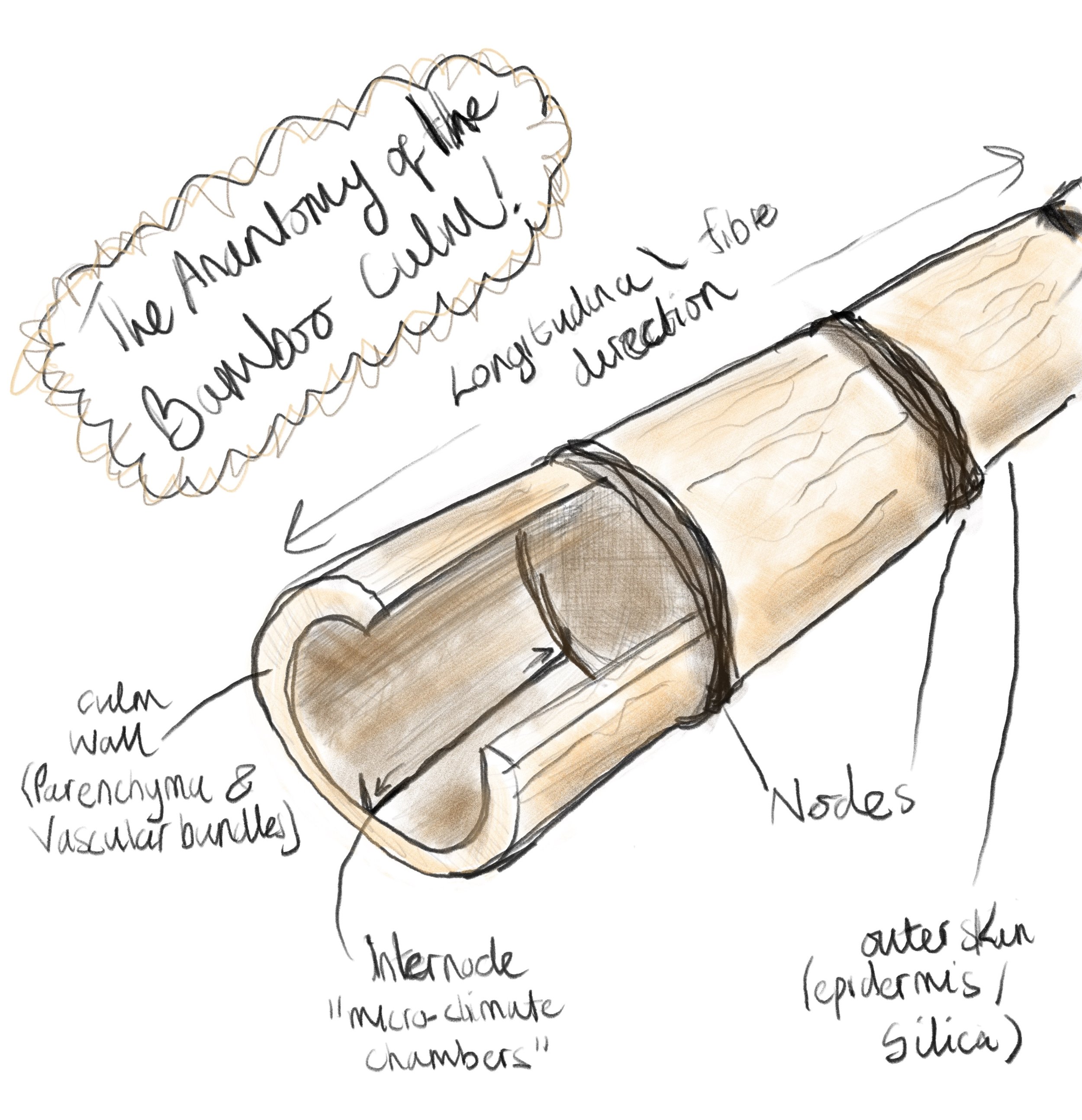

Bamboo isn’t a tree - it’s a giant grass! (Excuse my drawing/diagram for you all)

Its stalk (the culm) is divided into hollow chambers (internodes) separated by solid nodes. Nodes behave like internal bulkheads: they give bamboo its unique balance of lightness and strength, interrupt cracks, resist ovalisation, and help distribute load.

Because bamboo is a natural composite (equal parts fibre, silica, and lignin), it has an astonishing tensile strength for its weight. Those long fibres run the length of the culm and allow controlled flex under strain but can resist breaking under tension — perfect for risk-aware, responsive kinbaku when prepared, and used correctly.

Structure, strength, & wall thickness

Each pole tapers from a thicker base to a thinner tip. Wall thickness can vary along the length — thicker walls = greater load capacity and better resistance to ovalisation.

At Shibari Lounge, every pole is:

Selected by external diameter (typically 70–80 mm)

Checked for even wall thickness and alignment

Cut to 1.5 m or 2 m lengths for suspension work for optimum WLL

We never compromise the outer surface or inner structure (more on that below). The longitudinal fibres that carry load sit just beneath the outer skin; damaging or drilling through them reduces capacity and shortens lifespan.

Why bamboo cracks — and when it’s still safe to use

Cracking is one of the most misunderstood parts of working with bamboo. Even the strongest, best-treated poles will occasionally form fine lines along their surface, it’s simply how bamboo breathes.

Inside every pole, the solid nodes divide the hollow body into separate chambers, each sealed at either end. Once cut and dried, every one of these chambers develops its own “mini-climate” - a tiny pocket of air that warms, cools, and expands at a slightly different rate than its neighbour.

When the surrounding air gets warmer or drier, that trapped air expands and contracts independently, pressing outwards against the inner walls while the outer skin reacts to the room’s conditions. That pressure sometimes releases with a soft pop as the outer skin relieves tension creating a hairline crack that runs along the grain. It’s a natural form of equalisation, not necessarily a failure.

These surface-level cracks are usually shallow and follow the fibres that give bamboo its strength - They should run with the grain, not across it, meaning the long structural fibres that carry weight remain intact. In shibari use, this kind of cracking is normal and safe, provided it doesn’t deepen or widen.

(Can you spot the hairline crack here that runs over a node, this is a pole I personally decided to retire for suspension)

A pole remains fit for suspension as long as:

The crack is hairline-thin and straight with the grain,

There’s no visible separation or movement when under light pressure, and

The pole still sounds solid and feels rigid.

If, however, a crack widens, spirals, or wraps around the circumference, it means the internal fibres have started to tear and it’s recommended that pole be retired immediately.

Likewise, any change in tone (a dull “thunk” instead of a clear ring when tapped) or a faint creak under tension signals delamination inside. Those poles are no longer safe for human load.

Notes that bear in mind:

A hairline that crosses a node does slightly weaken the pole; only continue if you’ve confirmed it’s genuinely superficial and stable. If it passes through the node or opens under pressure — retire it.

Be mindful of rope placement. Rotate the pole so any superficial hairline sit away from any potential ropey contact and avoid snagging.

Why we DON’T drill or pierce bamboo for shibari practice…

You may hear some sources suggest drilling through nodes to release pressure and “prevent cracking”. While that can help airflow in decorative or architectural bamboo, it’s not suitable for load-bearing use.

Drilling interrupts the long continuous structural fibres, removes node-stiffening, creates stress concentrators, and can reduce bending capacity by ~30–60%. Under dynamic human load, that’s a hard no… (In my opinion and risk profile of course, each to their own)

For suspension work, we’d recommend leaving all nodes intact. Our focus should be on environmental control, careful preparation, and regular inspection — NOT modification.

And here’s why…

I can tell you at Shibari Lounge that the Moso Bamboo used to suspend from varies from 70-80mm in diameter, has wall thicknesses between 8-12mm and I have 2M lengths and 1.5M lengths to hang from. Using all of the weaker data (thinner walls, smaller diameter and longer bit of bamboo) to find our estimated Working Load Limits, it will look like the following;

2.0 m length: approximately 1.8–2.2 kN (180–220 kg)

For dynamic suspensions, you need to ideally aim for ~4× the body weight in the equipment being used, for example, 100 kg person → 4.0 kN (≈400 kg).

So If I was to hypothetically put a 6mm hole through the centre of my bamboo, I’d reduce it’s strength significantly, Shibari Lounge’s 2M bamboo pole now behaves like only ~0.34–0.55 kN (34–55 kg) one makes it kind of unsuitable for any dynamic human load bearing suspensions.

But that’s just one example and numbers are estimates - WLL will of course vary as it does with all natural products (like the jute majority of us tie with!)

Note: Different types of bamboo have different strengths, for example Guadua Bamboo Poles have a similar tensile strength to steel!

How else can you care for your bamboo?

Sanding

Lightly sanding is fine and sometimes completely necessary - especially if you find any rough bits around the nodes or where the bamboo’s been cut. You can smooth those edges out with fine sandpaper so your rope won’t snag, fray, or catch on sharp splinters. Just try not to get carried away…

Bamboo has a natural protective outer layer called the epidermis, sometimes referred to as the “silica” skin. It’s the glossy, almost glass-like coating you can feel when you run your hand along the pole. That’s where the bamboo’s natural waxes, resins, and silica are concentrated, forming a barrier that keeps moisture out and adds compressive strength to the fibres underneath.

It’s basically nature’s varnish — a hard, smooth armour that seals the bamboo from the elements.

Underneath that layer is the softer, more porous tissue — the fibrous structure that gives bamboo its strength. Once that’s exposed, it can start to absorb humidity, oil, and even tiny amounts of sweat from handling. Over time, that can cause the bamboo to soften, darken, and lose rigidity.

You’ll also notice that over-sanded sections often look dull or chalky compared to the natural golden sheen of the rest of the pole. That’s your visual cue that you’ve gone a bit too far. So, when sanding, treat it like skincare. You’re doing a gentle exfoliation, not a full peel. Focus on the cut ends and any raised lips around the nodes, and always sand in the direction of the grain. Once it feels smooth and clean, stop. You can always revisit it later, but you can’t put that protective layer back once it’s gone.

If you’ve accidentally over-sanded a small area, it’s not the end of the world — just be aware that part will be slightly more vulnerable. Keep it dry, avoid heavy oiling there, and monitor for hairline cracks over time.

Oil

If you decide to oil your poles, think of it as polishing, not feeding. Bamboo doesn’t need hydration the way rope or wood does. Its strength comes from being firm and dry, not supple.

The outer silica layer already does most of the work — it’s what keeps the inner fibres protected and balanced. When too much oil is applied, it can actually soften that surface and make the bamboo a little more pliable, which isn’t what we want for load-bearing. So, if you do choose to oil, make it light, intentional, and purely for texture or aesthetic reasons - not because it “needs it.”

Good options are Tsubaki and/or Jojoba oil (usually found in rope conditioning oils, great for the ropes running over the bamboo and the skin, win win!) - both are non-sticky, skin-safe, and very stable over time, so if you already have that on hand, you’re good to go, if you don’t… you’re in the perfect place to get some hand curated Sakunawa oil. Avoid heavier plant oils like olive or coconut oil, as they stay greasy, oxidise quickly, and attract dust.

To apply, add just a drop or two to a soft microfibre cloth and work it along the grain. You’re aiming for a gentle sheen, not a slick surface. The bamboo should feel clean and smooth, not wet or shiny. After a few minutes, buff it off completely with a dry cloth — the goal is to leave no residue. Essentially, use it sparingly for surface feel, be conservative and buff thoroughly.

Done right, this gives the pole a subtle glow, adds a little glide under rope, and helps maintain a consistent tactile feel between sessions. But remember, the best “conditioning” bamboo can get is simply being used. The ropes themselves do a natural job of polishing and maintaining the surface.

Beeswax

Beeswax can be lovely for maintaining bamboo if a whisper-thin amount is used lightly and with intention. It doesn’t soak in like oil; it simply sits on the surface as a protective film without “feeding” the fibres underneath and helps the bamboo resist dust and small humidity changes.

The beauty of beeswax is that it preserves the bamboo’s outer layer rather than smothering it. It keeps that natural silica intact, adds a gentle glide for rope movement, and gives the pole a soft satin sheen without softening the structure.

If you already use Sakunawa Rope Balm, you’re halfway there…

It’s a blend of beeswax and Tsubaki oil, both of which are safe for bamboo when applied sparingly. The beeswax creates a barrier, while the camellia oil gives a subtle shine and a smooth tactile finish.

To apply:

Warm a tiny amount of balm or pure beeswax between your fingers or on a soft cloth until it’s just pliable.

Rub it gently along the bamboo in small circular motions, focusing on high-contact areas. You only need a whisper-thin layer (less is more).

Leave it for a few minutes, then buff thoroughly with a clean, dry microfibre cloth until the surface feels smooth, dry, and clean to the touch.

You’re protecting, not coating. The goal is to leave no residue. If it feels tacky, cloudy, or greasy, you’ve gone too heavy - wipe it back with a dry cloth and let the bamboo rest.

Avoid anything with heavy solvents, petroleum waxes, or silicone blends, as these can clog the surface and stop the bamboo from breathing.

Done right, beeswax gives the bamboo that “cared for” feeling - firm, clean, and slightly warm under rope… without changing its strength or flexibility. It’s a lovely ritual for those who enjoy hands-on maintenance, but like everything in rope, it’s about balance and awareness rather than excess.

Flame curing

Flame-curing bamboo is a beautiful process — part science, part art form. It’s something you might see craftspeople doing in videos or at festivals, where they’re running a flame slowly along the pole until it turns golden or slightly caramelised. What they’re doing there is stabilising the surface — using controlled heat to harden and seal the outer silica layer.

The principle is simple: by gently heating the surface, you evaporate residual moisture and sugars within the top fibres. As the bamboo cools, those sugars crystallise and the skin tightens, giving it a harder, more resilient finish. Done well, this can slightly increase the bamboo’s resistance to surface cracks and help preserve its strength.

BUT, it’s not without risk. The outer skin of bamboo is incredibly thin, and heat travels fast through the fibres. If the flame stays too long in one spot, it can dry the pole unevenly or cause invisible micro-cracks just under the surface — the kind you might not see until much later when the pole is under load. It requires precision, patience, and a really good understanding of how heat affects tension in the fibres.

If you do decide to experiment at home, keep these things in mind:

Use a clean, steady flame such as a butane or propane torch — not a blowtorch or open fire.

Keep the flame moving constantly. Don’t hover; glide it along the pole in smooth, even passes.

Watch for colour change. You’re aiming for a warm honey tone, not dark brown or black. As soon as the bamboo starts to shift in colour, move on.

Let it cool naturally. Don’t wipe or oil it while it’s warm — that can seal in uneven tension.

Always test a scrap piece first. Every batch of bamboo reacts differently depending on age, thickness, and moisture content.

A properly flame-cured pole will feel harder, lighter, and slightly smoother to the touch, almost like tempered glass. But again — it’s not necessary for most rope practice. A stable, untreated pole in the right environment will perform just as well.

If you’re risk-aware and curious, flame-curing could be a rewarding way to personalise your equipment and learn more about the material itself — perhaps approach it as exploration, not necessarily as an upgrade.

A low-maintenance love letter to bamboo

Keep it simple — bamboo doesn’t need fussing. The ropes will do most of the maintenance for you. Every time they glide across the pole, they buff the surface, keeping it smooth and polished through use alone.

The most important factor in keeping bamboo healthy is the environment it lives in. It likes consistency. Keep it somewhere with a steady temperature and humidity — not against a radiator, and not in a damp garage or shed. Somewhere around 40–60% humidity is ideal.

Store your poles horizontally and supported along their length so they don’t bow. If you prefer to keep them upright, rotate them now and then so one side isn’t constantly under the same stress.

And lastly, don’t underestimate age. Like rope, bamboo has a lifespan. Over the years, the fibres fatigue and the surface slowly changes from repeated use. There isn’t a set expiry date — it’s about awareness. If it starts to feel different, sounds dull when tapped, or new lines appear, it’s time to retire it from suspension work and let it continue its life as décor, a floorwork pole, or a teaching tool… or errrmmm, other fun activities you can think of ;)

Caring for bamboo is about presence and connection — not perfection. Keep it clean, keep it dry, don’t over-hydrate, and pay attention to what it’s telling you. It’ll last far longer than you think if you treat it like a partner rather than a project.

From one kinbaku lover to another just wanting to understand the tools we use day in, day out;

Bamboo is one of the most remarkable materials we can use in shibari — light, strong, and alive in its own quiet way. It’s built from long, continuous fibres, sealed by nature with a glassy protective skin. It doesn’t need heavy treatments or deep conditioning; just balance, observation, and the right environment.

At Shibari Lounge and Sakunawa: The Shibari Shop, we choose to work with materials that hold meaning and integrity - the kind that respond to care rather than demand it. Understanding how bamboo behaves helps us tie, learn, have copious amounts of fun and build with more awareness and intention.

The love of bamboo isn’t about making it perfect. It’s about working with something that’s already beautifully imperfect — breathing, shifting, and evolving just like we do. Be risk-aware, not risk-averse. Keep learning from your equipment, keep listening to your materials, and let that curiosity feed your practice.

Bamboo doesn’t ask for much — just respect, patience, and the occasional dusting. In return, it’ll hold your art, your growth, and your people with quiet, enduring strength.

Thank you for reading,

Bex Tatsunawa <3